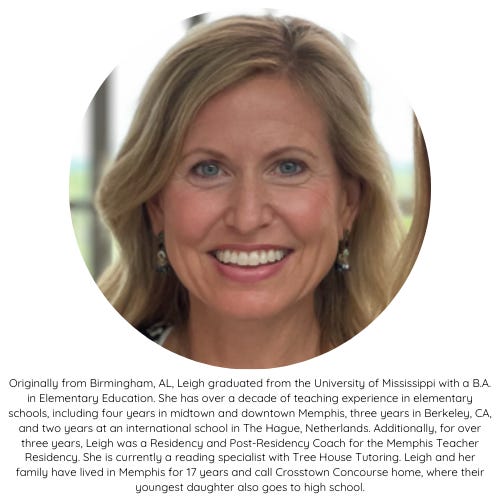

Today’s letter is a bit different than our usual letters. We are meeting one of my most brilliant, curious, hilarious friends, Leigh Richardson. Leigh is an educator who spent many years training teachers, but she did not realize she was dyslexic until she was 43 years old. When I recently learned this from her, I wondered how that was possible. So today I’m sharing Leigh’s story.

Instead of Leigh writing her letter, we decided to record our conversation and provide an edited transcript for our readers. You can listen below (my first attempt at recording an interview AND your chance to hear Leigh’s gorgeous Southern cadence!) or read the edited transcript. Either way, you'll learn much about dyslexia in kids and adults through Leigh’s journey. Statistically, dyslexia affects 1 in 5 people. So if you are not dyslexic, someone in your life most certainly is. —Anita

Click play to hear Leigh & Anita’s conversation

Anita: You and your husband, Todd, have two beautiful girls, Ava and Corinne.

Leigh: Yes, let’s see. Ava is 20 now and is about to graduate from the University of Memphis. As a young child, Ava was curious about school and reading and books, and she loved going to school and was super social, and continues moving in that same direction. Corinne is 15, and has started her freshman year in high school. And as a young child, she always loved being read to, but when it came to school and reading, she was very different than her sister. She did not have a desire to learn to read, and it was almost like she would have meltdowns if I even asked her to try to sound out any letters, or to even work a puzzle that had letters in it. But she loves school because she is social.

Anita: Did you attribute [Corrine’s] not wanting to read to temperament or did you think something was wrong? When did you suspect that Corinne might be on a different path?

Leigh: Probably when she was around age three. And I remember thinking that I found it strange that, well, she loved puzzles, whether it was a princess puzzle or a Dora the Explorer puzzle. But when I would pull out an alphabet puzzle, like those old wood letter blocks, she wouldn't want to touch it. It was like I put a plate of snakes in front of her. She had such a negative response. When she was four and five and with me being an educator, I thought I'm gonna get her going. So let's start looking at some of these very basic books, and she would have none of it. She would scream, pitch a fit, cry. And so I thought, okay, I know that I can't be the one to do this. With Ava, we sat down all the time. I just knew at age fourish [with Corrine], I couldn't do that.

We put her in a Montessori school, and a lot of Montessori schools, especially at that time, didn't have any kind of structured curriculum. So I wouldn't really get a lot of feedback from the teacher. She had the choice if she wanted to go sit and read a book at the Montessori School, and of course, she never did. For me, she still wasn't letting me help her, and I kept thinking, I cannot sacrifice my relationship with her over this reading, and I don't want to give her a bad taste in her mouth for print and books and language. And so I thought, well, let me wait until she gets to first grade, where she starts more of a traditional track. And I thought, hopefully she'll get some good phonics there, and then I can kind of see what is really going on.

Anita: And what happened in first grade?

Leigh: So about halfway through first grade, I just noticed that, again, her reading was not improving. She was struggling. And I thought something had to change. I went and met with the teacher to find out what her strategy was for working with Corrine. She was not teaching any kind of phonics skills. Her method of teaching Corinne to read was just to pull out low-level readers until Corrine could figure out how to read.

So that is when I really had to take matters into my own hands. Basically, Corinne would leave school to then come home and have to go back to school [with me] to learn to read. It was a miracle that she would let me teach her. It truly was a miracle, because in the past, she had not let me do any of this, but she was very agreeable to it, and I made it fun. We moved around. When teaching in a multi-systematic way, in a multi-sensory way, you're teaching them how to read, not only just by sitting down, looking at letters and sounds. But we've got letters on the floor, and we're jumping to different sounds, and we're watching maybe letter videos, or we may be writing. I may have sand on a tray, and she's writing out her letters using more sensory skills with the touch. And so by the end of first grade, her foundation of reading was where she needed to be at that time.

Anita: Did you suspect dyslexia?

Leigh: So that’s a great question.

I had always bought into the main myth about dyslexia: that somebody with dyslexia sees words backwards, reads backwards, writes backwards. And that is not true at all. I now know that dyslexia is a language processing kind of disability, and it boils down to being able to decode, basically, take small parts of letters and put them into a word. Someone with dyslexia has a hard time breaking apart those sounds, isolating those sounds. And then it can spread into having a hard time with fluency, having a hard time with reading comprehension, and having a hard time with grammar. It moves into those kind of bigger things. But where you start with a child with dyslexia is just breaking down letters and words that they really struggle with. So because she was making progress, I thought, well, she's not dyslexic.

And again, at the time, I didn't even think dyslexia in my head, because dyslexia is still relatively new. It's just over the past probably five years that it is really being talked about in the education world. And so when I was going through the School of Education at Ole Miss and teaching and doing all that, we didn't ever have a class on dyslexia. Like I'd heard about dyslexia, but I just again thought it was writing letters backwards, so I didn't know to suspect anything like that. So now let's move to second grade and see how she does.

Anita: Same school?

Leigh: Same school.

So we moved to second grade. Kindergarten through grade two is where children learn to read. They are reading. They are learning to read. And then third grade up, is when you are reading to learn. So I knew that she had one more solid year to hopefully get some good foundational reading skills that she could take with her to third grade and up. What I found out again was that her second-grade teacher, nor any other teachers on her team, had any kind of phonics, multi-sensory, systematic way of teaching these foundational skills. So I took it upon myself to keep building on what I had taught her in first grade as much as she would let me. But I knew something would have to change.

I happened to go to a yoga class over that Christmas break. And this particular yoga instructor walked in and said, “Okay, y'all, I have something that is so inspiring to me that I really want to share with you today, and it's about a paragraph that I have to read, but I just want to go ahead and tell y'all that I was that child in second grade that never wanted to be called on in class to read because I'm dyslexic, and so right now I'm gonna do my best to read out loud to y'all, but just so you know that.”

And as I laid there in child's pose on my mat, I thought, wait a minute. No, I AM that second grader that always would panic, thinking that the teacher was going to call on me. But does that mean I'm dyslexic? What does that mean?

And then after yoga ended, I stayed after and talked to the instructor for about an hour, asking her to help me understand what she meant by she's dyslexic, and she didn't like to be called on in second grade class. Because for me, I thought dyslexia just means you read backwards, and I never read backwards, and I never wrote backwards. And so she started kind of unpacking what dyslexia is, and by the end of that hour, I was flabbergasted, because I could identify with every single thing that she was talking about. Which meant that I was dyslexic. So I went home, and I just scoured the internet for several hours finding out more information about dyslexia. What are the signs of dyslexia in an adult? What are signs of dyslexia in a child? And one of the things I also learned about dyslexia is that it is genetic, so it runs in the family. And so I thought, well, if I'm dyslexic, then this is what we're dealing with with Corinne.

Anita: Did you feel relief, or did you feel….

Leigh: I was like, crying. I called my husband crying. I was just like you will not believe this, but after 43 years, I have learned that I am dyslexic and I can now take off, it makes me kind of tear up now, but I can now take off my hat of shame, because I have a word to identify what I struggled with for 43 years.

Learning about dyslexia also helped dispel some of the myths that people believe about dyslexia: the writing backwards, the reading backwards, the myth that dyslexics are dumb. People with dyslexia are at an average to above average IQ. It just means that we have a hard time with the initial language acquisition part of reading, the decoding. Dyslexia doesn't ever go away. If you're dyslexic, you're dyslexic. And dyslexia can look different for a lot of people. I can't tell you the number of people I've talked to as an adult and I explain about dyslexia, and they'll say, “I think I'm dyslexic. I think I was dyslexic. I always had a hard time with this or that, or my spelling was terrible, or I always hated to read.” But a lot of people can manage and get through it, and I did a great job of camouflaging my disability so that nobody knew that I was dyslexic.

Anita: How did you do that?

Leigh: You know, you fake it till you make it. A principal or boss might have said,”I’m going to give you five minutes to read this three-page article, and let’s do a round table discussion about it.” And I would think to myself, Okay, five minutes. That’s going to get me about three paragraphs in, not three pages. I struggled with reading comprehension. It just took me a while to get through anything. I could get through it. But it took me a while, especially if I wanted to comprehend it. I could read it as fast as everybody else, but I would not be able to have a productive round table discussion about it. So the way I would camouflage my dyslexia is that I would really know those first three paragraphs well. And I would think to myself, I'm going to chime in on the front end of this discussion to make it look like I really know what I'm talking about, when really I only know about a fourth of the information.

Anita: You adopted some behaviors that you didn't even know you were doing…

Leigh: Yeah, exactly, in order, to camouflage and fit in, right? Because we all want to fit in, and not do whatever it is that goes against what society says is the right thing to do. And so we learned, we learned to make our own path in order to get there.

Anita: So when you realized you were dyslexic, and you pretty quickly figured out that that must be the case with Corinne as well. What steps did y’all take with her?

Leigh: Right. So one of my good friends works at Bodine School [in Memphis], which is a private school that specializes in only teaching dyslexic children. And so I thought, well, let me reach out to her. So she just kind of held my hand through it, and she said, “Well, first thing you need to do is get an appointment with a psychologist to get Corrine tested so that we have that documentation. And then secondly, Corinne has got to start getting some of this formal teaching that's going to help her get through her next semester before she hopefully then will come to Bodine.” And then the next year she started at Bodine full time, and it was just a gift. I was so thankful that she was able to be saturated. And after two years, she was finishing up fourth grade, we felt like, okay, she's in a place now where she can mainstream back into a traditional school.

Anita: It seems like for kids, there's a lot of resources available in terms of, I mean, as you explain, now more than ever, probably not so much when [Corrine] was first diagnosed, but that seems to be changing. Is there anything you would say to an adult who suspects that they might be dyslexic?

Leigh: Yeah. I could be wrong but I think if an adult, unless they're in my same position, which was that my child struggled, and I learned through my child, I just don't think you might…

Anita: You might never know.

Leigh: I don't think so. In fact, when I had Corinne tested, I went back to get the results, and I sat down in that psychologist’s chair, and I said, “How many parents do you have that come in to get their child's test results that they also find out they too are dyslexic?” He said, “I mean, every single one of them. Every single one of them, because it is genetic.”

I think for me, knowing was a relief because I could take that hat of shame off and I could go, oh, one in five people in this world are dyslexic. I mean, that is the statistics. So I'm not broken, there's not something wrong with me. So I also could go, Wow, there's so many amazing people who have created and done so much for our world that are also dyslexic. Wow, I'm just like that. You know? I could go, Oh, no wonder I had a hard time.

I think for me, as an adult, just learning about that, being able to take the hat of shame off, and just healing from all those years. I have to say to myself, you don't have to hide anymore.

You know, I mean, you don't. You can say out loud if somebody's expecting you to read this or do that, or I could say, “You know what, I'm going to need a little more time because I'm dyslexic.” So I can now verbalize and state what I've struggled with and not hide it. So I think that, if anything, that's the

Anita: The gift of it, of knowing.

Leigh: I would probably say to an adult that you have to advocate for yourself, just like you would if you were in the classroom, and say, “Boss Jerry, I am dyslexic and I know you want this at this particular time and I’m going to do my best to get it at that time, is it ok if, or can I share the job with somebody else, whatever it is but you have to advocate for yourself and be upfront with whoever it is that is expecting something from you. If you are in a meeting with your boss and they are giving you information, record it so that you can then go home and then say I will follow up with you tomorrow about the conversation that we were having.

Anita: Yeah, when I have a little more time to process it

Leigh: A little more time to process and think about it. When I can read more about it and be able to pace it in the way that I want to

Anita: Yeah, which is why we are talking today

Leigh: Yes, exactly

Anita: Because it is a better way

Leigh: I can verbalize my experience better than I can write my experience. It would take me 5x longer to have to write all of this out vs being able to share it verbally.

Anita: Yeah. Awesome. I think we touched on everything. Thanks, Leigh.

Leigh: You’re welcome.

"In the middle of a disorder, know that a reorder is coming.”

A quote currently guiding Leigh, often attributed to Fr. Richard Rohr

Leigh’s Five Favorite Things:

Home. For the last eight years, our family has lived on the 10th floor of Crosstown Concourse. I never get used to the beautiful view north, looking over Memphis' gorgeous canopy of old-growth oak trees and the incredible sunsets to the west. The convenience of amazing food, art, live music and fresh flowers (at Mili's Flowers-a weekly splurge) is such a unique experience.

The Tell by Amy Griffin. Pretty sure I've never read a book so fast. This memoir explores Griffin's pursuit of perfection and her eventual search for answers through therapy and legal action, ultimately returning to her childhood home to confront her traumatic past. In her search for the truth to understand, Griffin explores what kind of freedom is possible if we accept our whole story and embrace who we really are.

The Science of Reading. This podcast delivers the latest insights from researchers and practitioners on early reading. Each episode takes a conversational approach and explores a timely topic related to the Science of Reading.

Memphis Wellness Collective: Acupuncture. Both my daughter and I have benefited greatly from this collection of independent, holistic wellness practitioners working together to offer whole-body wellness, relaxation and conscious care.

Sitting by the beach. Nothing beats sitting at the beach through the afternoon, sunset and dusk with a good book and a good friend.

I loved this form of letter using audio. I love the pivot and I am so enlightened. I think it's so brave to meet kids where they are in their educational journey. And to ditch the traditional way of learning for the method that is appropriate for them. It's also so incredible to have clarity at 43. I really enjoyed this today. Thank you!

I’m so grateful for Leigh’s willingness to share this story. It taught me a great deal, not only about dyslexia, but about judgement and labels. I hope more stories like hers come out so kids don’t feel that heaviness she felt for so long.